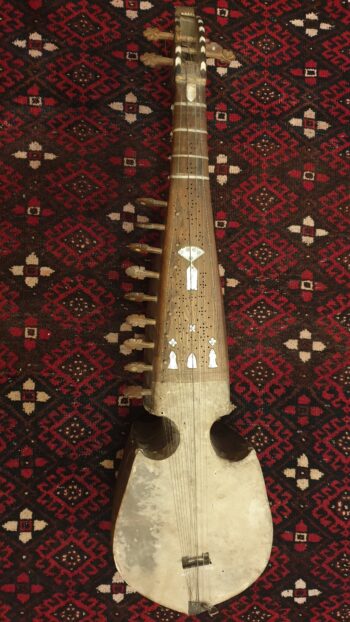

Photograph above: Minor touch-ups to a large rubāb purchased in 2011 in Kabul.

Photograph above: Different rubāb being restored or made

Photo above: An Afghan rubāb sold by ‘Adil entreprise’ and delivered as is. The head had to be glued back on and the skin changed. No compensation was offered by the seller.

Photograph above: An Afghan rubāb sold by ‘Adil entreprise’. The skin of the instrument had been pierced by one of the legs of the bridge because no provision or protection had been made for delivery.

Photo above: The use of natural glue makes it easier to remove a skin - all you need is water and patience to replace it.

Photo above: A completely improvised tensioning system to glue the head to the body of the instrument. The assembly was made using bone glue.

Photograph above : Old Afghan rubāb from Kabul (attributed to Juma Khan) bought in Germany in 2020

Photo above: Consolidation of the resonator and cleaning of damaged parts

Photograph above: Exterior cleaning of the wood, the instrument would probably have been kept in a damp place. It is likely that this rubāb was hidden underground to protect it from the Taliban

Photography above : After cleaning the wood, the original skin was replaced (in the right position) and all the strings were changed.

Photograph above: old Afghan rubāb mounted in five strings bought in 2022

Photograph above : The skin was in very poor condition and was replaced. The ankles were all replaced on the same model. They were made by Nadim Qaderi, son of Yusouf Qderi, grandson of Juma Khan.

Photograph above: Once the skin had been removed from the resonator, four open eggshells were found. These were glued to the bottom of the cavity, in a small ‘nest’ made from a small piece of tissue coiled along its length and gathered into a circular shape. Bone glue held everything in place.

Photo above: The finished instrument. It has been reassembled identically, with a double string for the chanterelle and the middle string and a single string for the bass. This Afghan rubāb is a very fine example of an instrument before the invention of the Kabuli rubāb.

Photograph above: rubāb or sarod bought at auction in Frankfurt. It's the first time I've seen this type of instrument, and its shape and workmanship are different from what is made in Afghanistan and Pakistan. I am unable to give a precise origin for this rubāb. The condition of the instrument requires careful restoration.

Photo above: The fingerboard was cracked. It had to be consolidated before being put back in place. I was very impressed by the finesse of the woodwork, which is very different from what I'm used to seeing on Afghan rubābs.

Photograph above: consolidation of the instrument's various chambers and the resonator's crosspieces.

Photographie ci-dessus : Un rubāb finalisé en France. Il s’agit d’un projet qui avait pour but de réaliser les finitions d’un rubāb afghan selon une toute autre technique et avec un outillage moderne de découpes électroniques. Le résulta tend à démontrer que le geste « traditionnel » du luthier est permet un travail plus rapide.

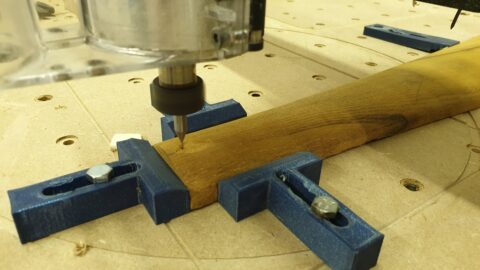

Photo above: The bone decorations were inlaid in a custom-made slot created by a numerically-controlled machine.

Photo above: This piece of work required a great deal of time to align and wedge the wooden part. The machine does not adjust its action as a luthier would. It would be simpler if the fingerboard were cut by a numerically controlled machine, before being made by a woodworker.

Photo above: The bone motifs were cut using a milling cutter mounted on a numerically controlled machine. The work was carried out directly on 2 mm thick bone plates.

Photo above: The bone pieces are glued in place using bone glue. A mixture of glue and wood powder was applied in a pore-filling process. The table is sanded to remove the excess glue.

Photograph above: the walls of the cavity are refined with a set of small planes. The initial work resulted in walls that were too thick. The idea was to improve the acoustics of the instrument.

Photo above: fitting the pegs. The pegs are cut precisely using a violin peg cutter. The pegs are positioned using a tool with the same cone as the peg cutter.

Photograph above: All the dowels are in place.

Photo above: Fitting the strings and making the final adjustments to the instrument.

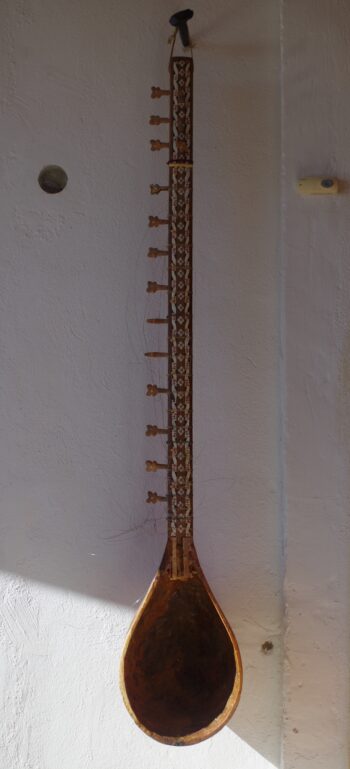

Photo above: An Afghan Tanbur made in Herat. The original soundboard was cracked in several places (instrument delivered in poor condition). Cleaning and consolidation of the damaged wooden parts.

Photo above: Fitting the new top after surfacing. The top comes from Peshawar and was made by a Pashtun luthier called Akbar Ali. The mulberry tree used came from Kabul, chosen for the quality of its tight fibres. It was assembled using bone glue. Bicycle inner tubes were used to hold the instrument in place; the elastic properties of this material make it ideal for this type of assembly.

Photo above: The new soundboard gives the instrument a beautiful resonance, even before the strings were fitted.